The Data Doesn’t Support Blaming Laptops: A Critique of “We Gave Students Laptops and Took Away Their Brains”

When correlation meets confirmation bias: Why the evidence for technology-caused cognitive decline doesn’t hold up

The Free Press recently published an excerpt from neuroscientist Jared Cooney Horvath’s new book, “The Digital Delusion,” with a provocative headline: “We Gave Students Laptops and Took Away Their Brains.” The article’s central claim—that “decades of data show a clear pattern: The more schools digitize, the worse students perform”—has been quoted on X by parents and educators.

As someone who studies educational technology and analyzes education data regularly, I disagree. While thoughtful technology integration matters tremendously, this article commits multiple statistical fallacies and misrepresents the very data it cites. The evidence doesn’t support blaming laptops for declining test scores. It actually points in a completely different direction.

The Data Horvath Cites May Not Exist As He Describes It

Here’s a fundamental problem: the article states that “In 2012, 2015, and 2018, PISA asked students how much time they spent using digital devices during a typical school day” and presents a chart supposedly comparing screen time and performance across these years.

But according to OECD documentation, PISA didn’t ask this specific question consistently across those years.

What actually happened:

PISA 2012, 2015, 2018: Had an optional “ICT Familiarity Questionnaire” with varying questions about technology use, not all countries participated, and questions changed between cycles

PISA 2022: First time systematically asking students to report “how many hours per day do you spend on digital devices for learning and leisure activities at school”

The 2015 OECD report “Students, Computers and Learning” analyzed 2012 data, but it didn’t ask the identical question Horvath describes. The ICT questionnaires asked about general computer use, not specifically daily hours broken down by learning vs. leisure at school.

This creates a major credibility problem: Horvath presents a chart supposedly showing consistent correlations across 2012, 2015, and 2018, but the data to create such a comparison, using identical questions and methodology, doesn’t appear to exist.

Either:

He’s conflating different questions from different years as if they measured the same thing

He’s presenting analysis from the 2015 report (based on 2012 data) as if it represents multiple years

He’s combining data from incompatible sources

The Most Recent Data Actually Contradicts the Article’s Central Claim

Here’s perhaps the most damning evidence against Horvath’s thesis: the newest and most comprehensive data on in-school technology use shows the opposite of what he claims.

The article presents this dramatic narrative: “The more time students spent on screens at school, the further their scores fell.”

But look at what the actual PISA 2022 data shows:

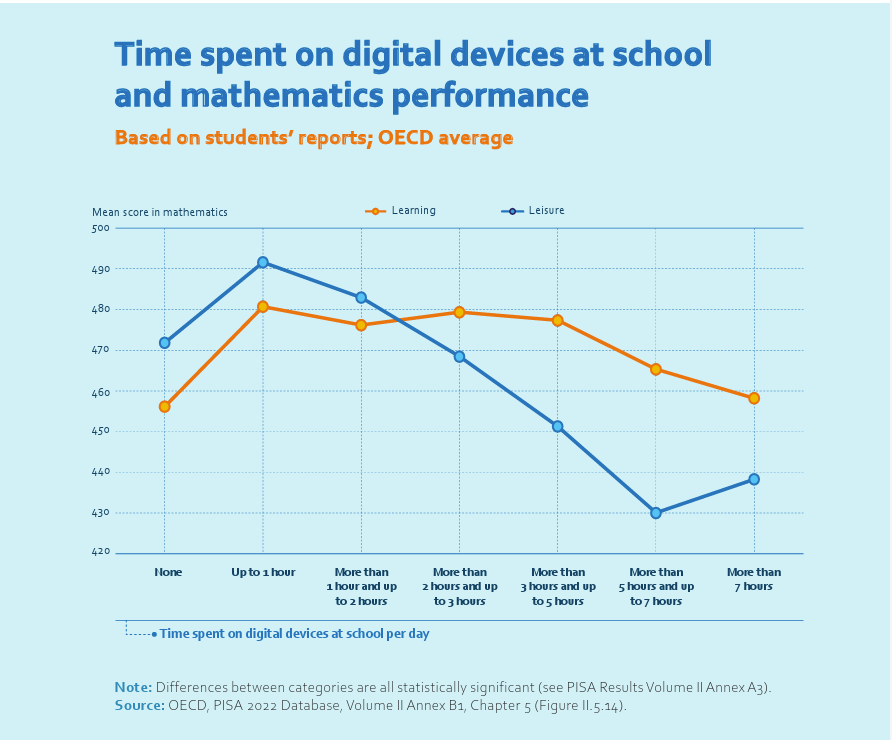

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Volume II Annex B1, Chapter 5 (Figure II.5.14)

For learning purposes (orange line):

Students with NO digital device use at school: 456 points

Students using devices up to 1 hour for learning: 481 points

That’s a 25-point INCREASE associated with moderate educational technology use

The data shows a clear pattern:

Zero technology use: lower performance (456)

Moderate use for learning (1-3 hours): highest performance (476-481)

Only extreme use (5-7+ hours): declining performance (459-465) However this is still above the zero technology usage numbers.

This is not the linear “more screens = worse outcomes” narrative the article presents. The optimal amount isn’t zero. It’s moderate, purposeful integration.

Even the leisure use line (blue) shows an inverted U-curve: students with moderate recreational device use (up to 1 hour) score higher (492 points) than those with zero use (471 points). Only excessive leisure use (5-7+ hours) shows the dramatic drops Horvath emphasizes.

This completely contradicts the article’s central thesis. The most recent, comprehensive PISA data on in-school device use, from 2022 which is the first time PISA asked about daily device time at school shows that thoughtfully integrated technology for learning is associated with better performance than no technology use.

The real story isn’t “technology bad.” It’s “how and how much matters enormously.”

The Bottom Line

The article’s central narrative, that decades of school digitization have caused decades of cognitive decline, is contradicted by the very data sources it cites:

The data he claims to have doesn’t exist in the form he describes: PISA didn’t ask consistent questions about daily screen time hours at school across 2012, 2015, and 2018

The newest, most comprehensive data shows the opposite: PISA 2022 reveals that moderate technology use for learning is associated with higher performance than zero technology use

An important caveat: the PISA data showing negative correlations with screen time largely reflects leisure and recreational device use (social media, games, entertainment), not purposeful instructional technology integration for learning.

Source: OECD, 2024, p. 9

Does this mean technology in schools is perfect? Absolutely not. Does it mean we should stop asking hard questions about screen time, distraction, and learning? No.

But it does mean we need better evidence than what’s presented in this article before we conclude that laptops are “taking away our children’s brains.”

The data tells a different story: The relationship between technology and learning is complex and context-dependent. It’s not the simple “more technology = worse outcomes” narrative this article presents.

Let’s focus our energy on understanding how to integrate technology effectively rather than misattributing complex educational challenges to laptops that have been in schools for decades without causing measurable harm until the pandemic disrupted everything.

As someone pursuing a doctorate in educational technology, I believe rigorous evidence should guide our decisions about technology in schools. That means honestly engaging with data, not cherry-picking correlations that support predetermined conclusions.

Sources cited:

National Center for Education Statistics, TIMSS 2023 Results (December 4, 2024)

OECD (2015), “Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection”, PISA Report based on 2012 data

OECD (2024), “Students, digital devices and success”, PISA 2022 Report - Volume II

OECD (2024), “Managing screen time: How to protect and equip students against distraction”, PISA in Focus No. 124

OECD PISA Database: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/programmes/pisa/pisa-data.html

[Comments are open. I welcome thoughtful pushback and additional evidence that would challenge or support this analysis.]

Outstanding takedown of confirmation bias in edtech discourse. The inverted U-curve from PISA 2022 is the smoking gun here, moderate integration beats zero tech, but gets buried by people hunting for a simple villain. The part about inconsistent questionnaires across years is brutal, you cant construct a longitudal trend from incompatible instruments. This happens constantly in policy debates where people cherry-pick cross-sectional correlations that fit their priors.